Bridge Wire: High-Current Ignitor Construction

The "exploding bridge wire" is commonly used as the core of an

ignitor. Electric current is passed through a thin wire, making

it get really hot. Thus it ignites whatever pyrogen is placed

next to it.

The following bridge wires can be

fired

with a 12 volt car battery, such as is commonly used at rocket-club

launches.

At home I use 110volt AC house current through long drop cords, lending

credence

to the term "exploding bridge wire." They burst with enthusiasm.

These are for ground-based

ignition only, where lots of current is

available.

They will NOT fire from a 9-volt battery, so DO NOT attempt to use them

with your

altimeter or staging device!

Materials and equipment:

Well, I don't really need all of this stuff but I am a junk freak,

and most of it will be used before this project is finised.

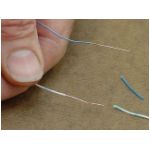

The bridge wire is the interior of a lamp cord. Stripping the

insulation from 6 inches or so to reveals 40 or 50 very thin

strands.

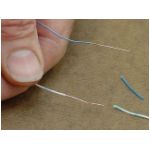

These measure .006 inch on my caliper. Separate one strand from

the

bundle and draw it through the superfine sandpaper until it

gleams.

This will make soldering much easier. Sand gently, especially if

using the "coarser" 320 grit sandpaper, as these strands break very

easily. 600 grit is ideal, if you have it.

The computer geeks at my workplace are always throwing out sections

of network cable. I lurk around the corner, sneak up to the trash

pile, grab a cable, wrestle it to the ground and subdue it with a

knot.

Whew!

A sharp knife is used to slit the covering two or three inches down,

revealing four pairs of wires, neatly twisted together. Hence the

name "twisted pair" cable. They are nicely color-coded, and are

ideal

for making these ignitors.

Then I pull and pull to get more of the covering off. This is

a lot of work, partly because there isn't much to grip, and the

covering

tends to break if you go at it too hard.

Once a foot or two is stripped, I tie the covering to something sturdy

and use both hands. This makes it easier to apply just the right

pull.

Here I have cut 2-foot sections for 8 potential ignitors. I like

to start with long wires. They can be re-used by cutting off any

damaged sections after use. Long, virgin ignitors are good for

launches.

Short, experienced ones are fine for static tests and ignitor

experiments.

This saves a bit of work.

A knot is tied 4 to 6 inches from one end. The wires are

untwisted

up to the knot, knot keeps them from separating any further.

About

1 inch of insulation is stripped from each wire. Sometimes I

wonder

if I should wait on this, for safety purposes to prevent accidental

ignition,

and to keep the wire clean until launch time. Then I get paranoid

about coming up to the launch stand without a wire-stripper, so I go

ahead

an strip them.

Now to the other end, where the bridge wire will go. The wires

are untwisted about 2 inches, and one of them is cut 1/2 inch shorter

than

the other. About 1/8 inch of insulation is stripped from the end

of each wire. If a stripped end is not shiny, sand it or scrape

it

clean!

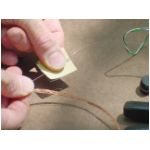

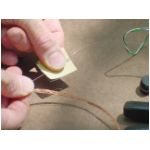

The fine bridge wire is wrapped 3 or 4 times around the stripped end of

the short wire. Apologies for the last picture, the wire had

slipped

partly off. I corrected this error before soldering, but forgot

to

get a photo.

These thin wires are pretty squirrely to handle, so I find it better

to clamp down the soldering iron and bring the wires to it.

Tug gently on the bridge wire after soldering. If it slips

off, it didn't get soldered. Do it again.

Now twist the wires back together, at least as tightly as they were

before. This is to reduce the strain on the thin bridge

wire.

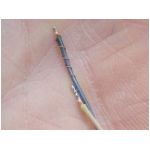

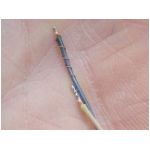

Wrap the bridge wire strand around the longer wire 4 or 5 times on the

insulation, then 3 or 4 times on the stripped end. Solder the

end.

Now I like to trim the loose ends, usually cutting off a bit of the

network

wire at the far end, and getting rid of any frills at the shorter

end.

Isn't it pretty!

Not a bad idea to test these with the voltmeter for continuity.

But I usually don't. They invariably work at this point.

More

important is to test one just before an important firing, to be sure

the

slings and arrows of time and travel have not broken the bridge or

compromised

a solder-joint.

Longer ignitors are wrapped around three fingers. Shortish ones

around two. This makes it easy to find the right length on the

first

pick.

So here is today's production. Took me about an hour to do

this.

Some folks prefer to buy ignitors. That is fine with me. I

prefer to make everything I can.

To be an effective ignitor, these will need some pyrogen. That

web page is coming, but the short of it is: wrap the bridge-wire

end in masking tape with 1/4 gram of black powder. Add a few

magnesium to titanium

turnings for more heat. These work very well with my candy

motors. I am testing fuse

paper for use as the ignitor pyrogen. It is exceedingly cheap

and easy, and in my tests so far has worked quite well.

Question: Why

aren't you using Nichrome? Isn't it better?

Answer: It isn't needed when

plenty of current is available. And copper is virtually free,

pretty, and solders easily.

These ignitors have proven very reliable for me. In several

hundred tests over the last three years, I have had a few ignition

failures. All of them have occurred either because the pyrogen

did not ignite the propellant, or because the power did not get

delivered to the ignitor. Not once has the bridge wire failed to

ignite the pyrogen. It's hard to imagine how nichrome could be

better in that regard.

Nichrome is better is when current is limited, such as in

flight. Using very fine nichrome wire, one should be able to make

ignitors like this which could fire from a small battery. Thus

they could be used with battery-powered altimeters, timers, or staging

devices.

But I have another cheap and easy

trick for that...

Jimmy Yawn

jyawn@sfcc.net

9/15/03

rev. 4/13/05

Recrystallized Rocketry